Healthcare in Cuba: failed experiment in socialised medicine, or something else?

Cuba as a public health outlier

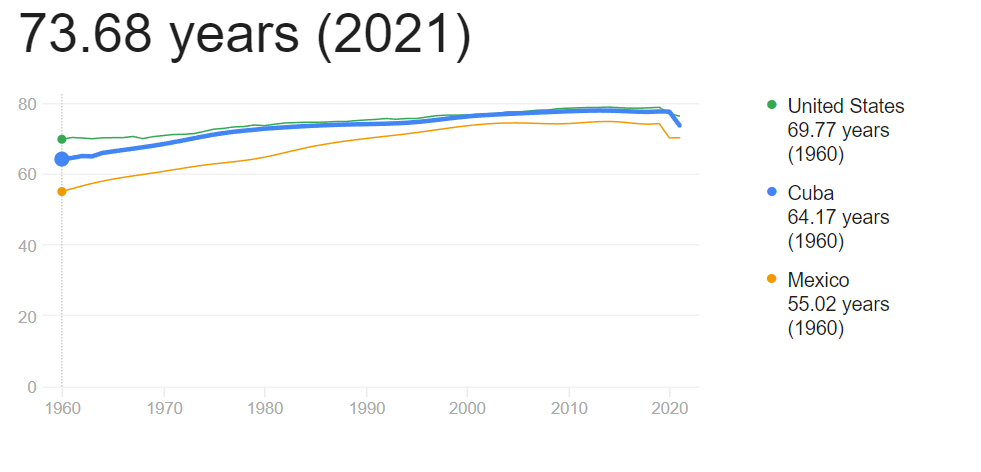

Cuba was one of the public health outliers we learnt about in university. Small country, limited wealth, cut off from much of the world economy. Yet, somehow managing to make much with what the country had. As we saw in our last blog , Cuban life expectancy at birth, the average length a child born can expect to live given current mortality rates, rivals many high-income nations. In fact, look at the chart below - since around 1980, the country has performed similarly on its life expectancy to the USA. Yes OK, we’re maybe setting the bar a bit low with a country with a notoriously low life expectancy , horrendous inequality and an appalling mismatch between the wealth it generates and benefits for its citizens. But there’s still something worthwhile about the comparison.

Compare this similarity with the stark disparities in the economies of the USA and Cuba, and the picture starts to become clearer. Somehow, a country isolated from the world economy, with limited resources, is managing to sustain its citizens to living a very reasonably long life. I think it’s worth exploring - and have been reading ‘Cuban Health Care - the ongoing revolution’ by the author Don Fitz, whose daughter went to the Latin American School of Medicine in Havana. It’s well written, if what feels like somewhat of a propogandous-mouthpiece for the regime at times, so am going to attempt to walk the narrow tightrope of tackling this from an evidence-based view, while accepting it’s a hugely politicised space and any clash of ideologies here is going to be somewhat unavoidable.

Healthcare in Cuba post-1959

On 1st January 1959, Fidel Castro overthrew the government of Fulgencio Batista following an armed rebellious struggle since 1953. Castro’s government shortly after nationalised the economy, centralised the media, and consolidated political and civic institutions.

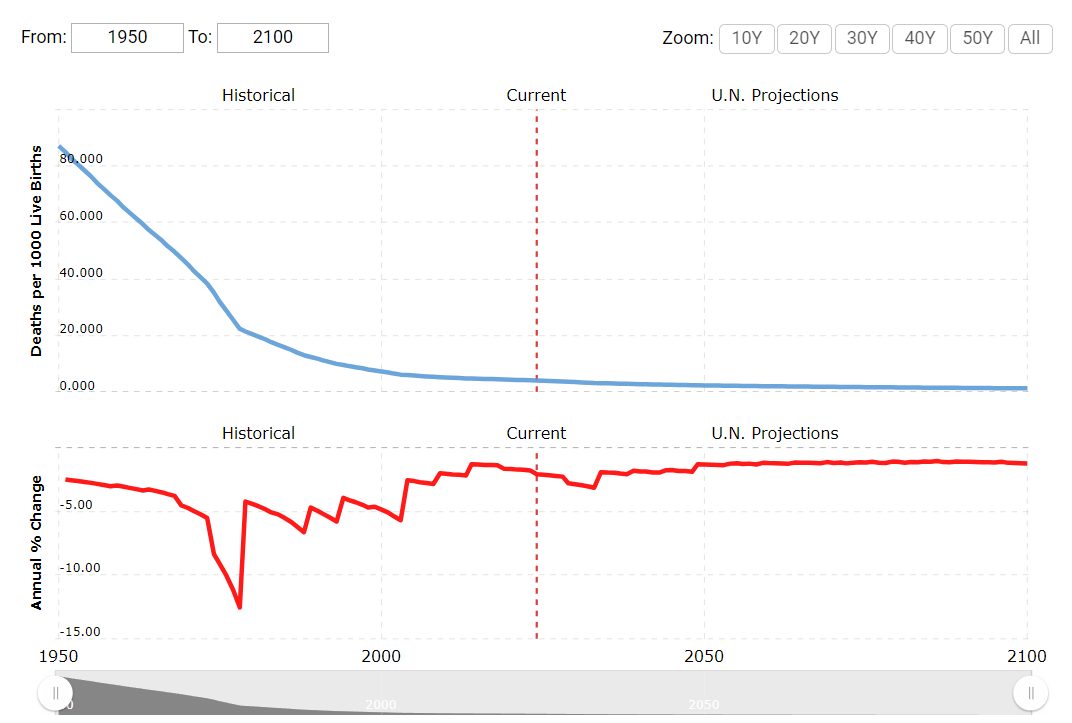

Following the revolution, around half of the 6000 doctors then in Cuba left the country. Such an exodus must have put enormous strain on the healthcare system, likely not captured in routine statistics at the time which suggest for example infant mortality (deaths in children under 1) - a good measure to test health system quality - actually continued to fall after Castro came to power.

Castro’s government began a number of changes in healthcare training and service delivery. New healthcare centres and hospitals were built, private, mutualist healthcare organisations were integrated into the public system, mass vaccination campaigns aimed to protect citizens from infectious diseases, while undergraduate medical training saw both an expansion in places, with a new focus on social medicine, supported by deliberate recruitment of students likely to support a new approach to practising medicine that conformed more to the regime’s preventative, holistic and social justice agenda. Alongside this, wider changes to reduce illiteracy, distribute food more equitably, and other social programmes likely had an influence.

The Cuban Polyclinic

Mention polyclinics in the UK and you’ll get a groan. Ara Darzi, a former surgeon, pitched the concept as a way of integrating primary and secondary care services and improving access in general in the ’00s. Polyclinics would house primary care services, specialist clinics, allied healthcare services and any number of wider functions such as urgent care/walk-in facilities, community diagnostics and services from councils. Plans were eventually shelved for a roll-out of these across England after BMA opposition (who decried the potential for large-scale privatisation of the centres), expensive capital costs, significant pressure on walk-in centres, a lack of engagement with communities on their need, and other reasons .

Let’s focus for a moment back on Cuba though. Polyclinicos Integrales were developed in the early ’60s in Cuba with the aim of unifying preventive and curative medicine, through a network of primary care centres in communities. Staff at polyclinics were to include at least one general practitioner, nurse, paediatrician, an obstetrician/gynaecologist and a social worker, with dentistry added to the polyclinic workforce shortlty after. Staff at the centres paid proactive visits to residents in their area, an activity Fitz credits with a reduction in hospital service use over the same period. I couldn’t verify the data, but between 1965 and 1969 community visits by polyclinic staff doubled, whereas hospital visits (unclear admissions or clinic appointments) dropped by 9%.

In 1974, Polyclinicos Communitarios were conceptualised, aiming to strengthen integration of the staff working in the polyclinics, with a renewed focus on home visits in the community. Dispensarizacion, a kind of outreach, was developed, where staff would actively look for conditions that affect key groups in the population (e.g. children, women, the elderly), with visits representing a significant proportion of the working week. Alongside this, staff were expected to work with community groups on health education and promotion, and the polyclinics became more embedded in undergraduate and postgraduate education. Community participation has been key, with local committees charged with mobilising the public to support the government’s wide-ranging social programmes key agents to local health initiatives, from health promotion to mass vaccination campaigns.

Later, consultarios were created: smaller, doctor:nurse teams based in communities serving neighbourhoods in clinics and patients’ homes, referring to polyclinics when more complex care is required. Prevention remains key, as does a focus on the social determinants of health, with staff apparently well versed in assessing for and supporting service users with issues in their wider life, ranging from housing, the environment and others, as they are in addressing more conventional medical issues.

Training a new cohort of socially-aware health professionals

The aspect that grabbed me the most from the book was the idea of selecting aspiring health professionals with a desire to work for social justice, alongside aptitude as a future clinician. The Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) appears to have done just that, focussed on recruitment from those with backgrounds typically either financially prohibited from studying medicine, or less encouraged due to stereotypes that medicine is a vocation for the more wealthy. The curriculum places a strong focus on health equity and the social determinants of health, as well as making clear the value (yet also prestige) of primary care as a career choice.

Some critical thoughts

As I mentioned, the book itself is worth a read, but gives little in the way of a balanced view. Recognition is made in the book of the large investment the Soviet Union gave to Cuba after the revolution, without which the island would have struggled to recover and rebuild its healthcare system and institutions. As the USSR collapsed in the early ’90s, Cuba was forced to diversify its economy, which to be fair it remarkably managed to while keeping its services functioning. Developing and running a workforce and healthcare system, never mind the wider public services and programmes the government ran during the period, literally costs millions. Take a look at the graph above and you can see the country’s inflation rate rocketing, which as well as affecting people’s health through what they can and can’t buy, will affect purchasing power for healthcare delivery. So, the economy is critical, which it always is right?

Also, it’s clear from wider sources that ongoing economic challenges continue to affect the healthcare system, with supplies, equipment and medicines in extreme short supply . Staff are reportedly paid poorly, potable water is in short supply at times. Some of the aspects of the programmes above do ask a lot of the staff running them - the doctor:nurse teams were expected to literally live in the communities they work, some of them being called on at night. I’ll circumvent for now the expectation of foreign service Cuban doctors are expected to embrace, which on many levels if admirable in promoting their duty to support communities in need of healthcare around the world, but also has left them participating in a number of armed struggles worldwide, with a somewhat hazey separation betweeen their duty as doctors, and their role in military conflict (even if the struggles they participated in were often against questionable regimes/dictatorships, US-backed or otherwise).

The book also says little of the quality of life of Cuban citizens living in receipt of these healthcare services - what’s it like to live in a communist nation, isolated in certain ways from the rest of the world? Happiness and political freedom probably trump living a long life, meaning we’d need far more evidence to understand the Cuban context.

One thing is for sure though. Cuba has proven a country does not need an abundance of money and resources to achieve universal education, quality public health, a sound infrastructure for healthcare delivery, and mass participation in health and healthcare. There seem several lessons we can draw for our own services and health system back in the UK and Wales - so is it worth putting aside our biases, and thinking genuinely what we could bring back from such settings?

Jonny, Co-Director HCB Associates