Primary care in Brazil - the Brazilian Family Health Strategy

Day 1 PHA5 in Mar Del Plata

It’s day 1 of the 5th People’s Health Assembly in Mar del Plata, Argentina. The crowds of around 900 arrived from countries across the global South and North arrived late into the night last night - friends and comrades embracing, smiling, laughing. It’s a beautiful sight too this morning with the sun rising over the sea, the conference at a small beach town that a friend and I thought had tones of Bournemouth/Weston Super Mare, with obviously a Latin twist.

I’ve got Matt Harris to thank for this blog. OK, and a few morning coffees too. Matt and I have spoken on and off for years since I saw him pitch, to a room of GPs at a Royal College of GPs conference in Glasgow, the idea of deploying community health workers in the UK. North Wales of all places. Community health workers are typically recruited from the area they work, form part of the core primary care team, have training in key, simple health tasks, and have a cohort of households whom they visit either proatively, looking for unmet health needs (vaccination, chronic diseases, and wider), or reactively, for example being first contact for unwell children.

The pitch, later to the National Institute of Health Research panels who were to make the decision on the research idea, fell down at a late hurdle. Matt has advocated ever since for the community health worker programme, recently succeeding in attracting investment in London , drawing attention to their success, also around the rest of the world, but particularly as part of Brazil’s health strategy since 1994.

This blog is less about community health workers in general, but a brief overview of some of the changes brought in to improve public health and primary care delivery in Brazil, looking into, as we’ve done in previous blogs, what we could take back to Wales and the UK from South and Latin American health systems.

Brazil’s Family Health Strategy

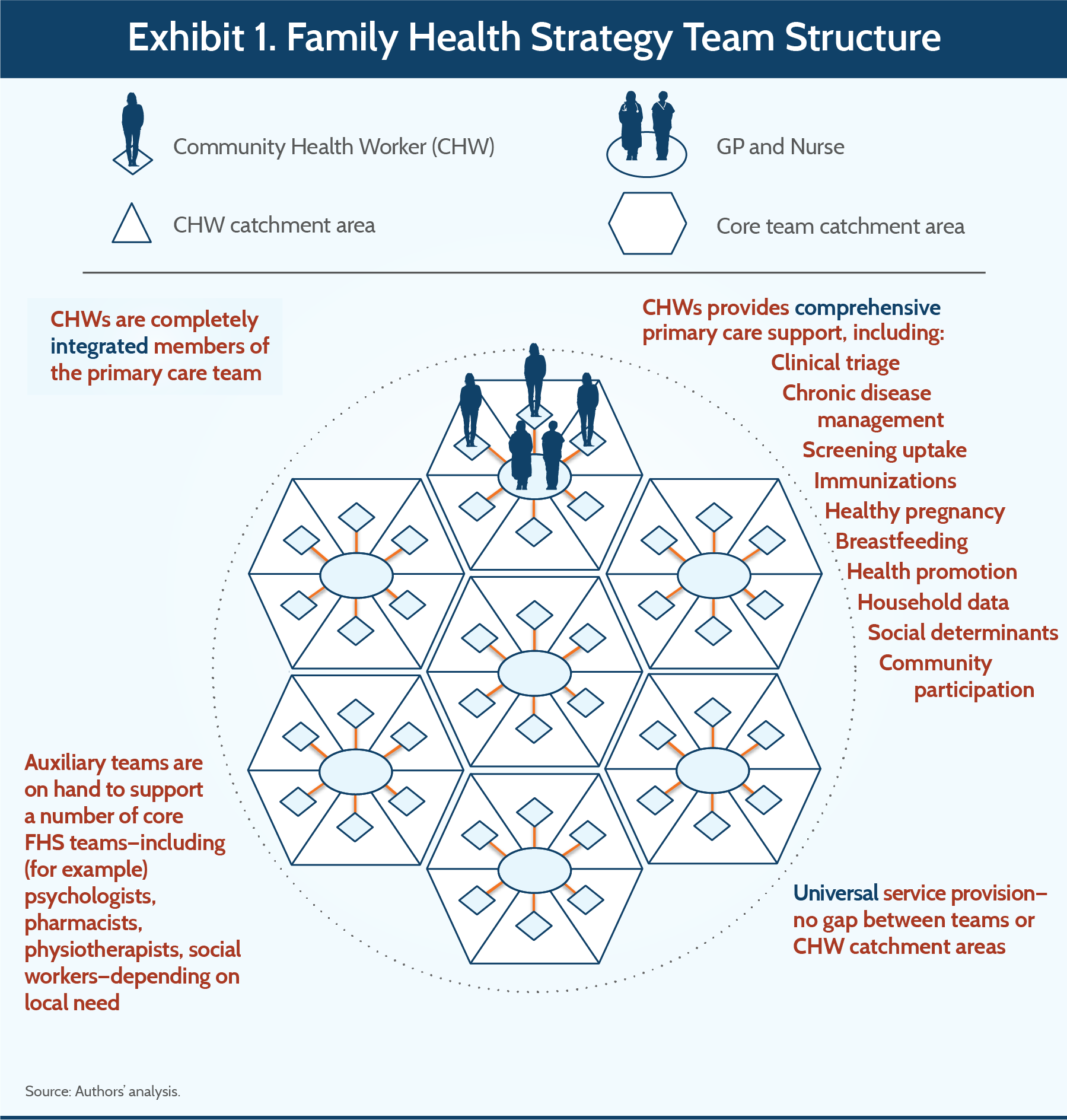

Brazil recognises, much like several other South American and other countries, health care as a constitutional right . In the 80s and 90s though, the government recognised an over-reliance on secondary care, and so began in 1994 a federal programme to provide integrated primary care. At the heart of this strategy was the roll-out of teams comprising a primary care doctor, nurse, and 6 community health workers (see image below). Other professionals linked in, including psychologists, pharmacists and physiotherapists, with the teams covering around 3-4000 people - each community health worker being assigned to up to 150 families.

***from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case-study/2016/dec/brazils-family-health-strategy-using-community-health-care-workers ***

Households would receive at least one visit a month from a community health worker, maximising the quality of health data on the population, helping people understand their health conditions and treatment, and the community health worker liaising closely with the wider primary care team. Community health workers took on a wide variety of roles ranging from health education, health promotion, community development, healthcare navigation and more.

Other developments took place under the Family Health Strategy around the same time, including increased investment, improved coverage by the public healthcare system (meaning people no longer had to pay for care), conditional cash transfer programmes (people receive money if they participate in a social programme, for example prenatal care or childhood immunisation), making it somewhat tricky to distinguish what programme had the greatest effect. This review suggested the strategy had clear favourable impacts on child mortality, and potentially on reductions in hospital admissions from conditions linked with the quality of primary care quality.

Implications for the UK

Reports of Brazil’s strategy suggest progress towards universal coverage of the policy remains uneven, due to issues such as recruitment (doctors remain keener on training as hospital specialists), preferences for private healthcare among more affluent population groups, creating a two-tiered healthcare system and poor integration between primary and secondary care records and data. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it. Yet, once again we have a health system and government clearly focusssed on primary care, on public health, and succeeding over a period in fulfilling its aims of improved equity, prevention of avoidable health problems, all through investment and strengthening of primary care.

These achievements haven’t arisen spontaneously - as a Lancet Americas article makes clear, it’s been due to the toil and collaboration of both public health professionals but also trade unionists, activists and others, all part of the Health Reform Movement promoting reform of the health system to realise the constitutional right to health recognised in Brazilian law. The reforms continue to be tested by global institutions such as the World Bank, keener on participation of the private sector, with domestic challenges also, for example under the Bolsanaro administration (2019-2022).

Once again though Brazil has shown, with investment, a focus on primary care, integrated healthcare teams, embedded in communities, and a proactive approach, healthcare and public health outcomes, and their equity, can be significantly improved. Bit of a pattern here isn’t there?

Tomorrow we’ll look at Costa Rica, admittedly a more affluent nation than the countries we’ve looked at so far, but nevertheless with clear lessons for primary care systems back in the UK.

Keep an eye out also obviously for some video and audio coverage of the PHA…

Jonny, Co-Director HCB Associates

PS if you’re interested in global health, what we can learn from other countries and some of the politics and debate surrounding why we often fail to appreciate and learn from a wide range of health innovations in other countries, I’d recommend Matt’s book Decolonising Healthcare Innovation (see here ). Matt discusses his experience of trying to promote aspects of the Brazilian healthcare system back in the UK, and more widely summarises much of the bias and exclusionary practices of health research, innovation and investment, and outlines a series of examples of innovations that could show promise in the UK, as well as explaining how frugal innovation, or knowledge transfer from settings with limited financial resources, could be better promoted.